Karate

Necessarily, as this is a website and not an encyclopedia, this will have to be a precis version of the history of Karate; in it’s fullest detail it could fill volumes of encyclopedia and then still have bits left over! Without going back into the mists of time and studying its Chinese antecedents and influences, we can start with the foundations of what most of us practice today, which is Japanese Karate, and these are the various systems, geographically derived from what we know today as Okinawa, but more traditionally as the Ryukyu islands. Long a prefecture of Japan, the islands had indigenous systems of combat which, broadly, divided into Naha-Te, Shuri-Te and Tomari-te, themselves the building blocks of Shorin-Te and Shorei systems.

Any history of an art, or literary period is often more about the people as much as the product and no more so is this the case than when studying the development of Karate as we know it (in it’s various guises) in the West today. Therefore, alongside this history is a geneology of the known and recorded Karate masters. Shuri Castle

As Western Karateka we are likely to have prejudices, developed in the main from the ‘style‘ we have practised over many years and, in too many cases been brainwashed (I mean this in it’s less contentious sense) about the rigidity of a ‘style’ and by far the greatest impediment to properly understanding and, therefore, developing the art is to approach it as if it’s an insect from the age of the dinosaurs, visible to all, but ‘frozen‘ for all time in amber.

Endless numbers of people have learned and re-shaped Karate, each person having a social, educational, and physical background and instructor influence that has meant a very ‘personalised‘ approach to the techniques handed down over the past hundred years, or so. Sadly, the western approach, of the past 50 years or so, has been to codify these styles in such a way as to equate adherence to a narrow style interpretation of the art with control of the student and instructor population. This overview of karate and it’s key players only re-enforces how very much this is an ‘individual influenced‘ game, whether it has been Itosu Anko structuring the Okinawan systems to fit into a school programme or Funakoshi Gichin codifying it still further to fit into a Japanese University curriculum – needs must when society and politics demand.

Anko Itoso

Anko Itoso

We have mentioned Funakoshi, often portrayed as the father of modern Karate (which is partially true as it developed in japan), but that accolade should, more correctly, be attributed to Itosu Anko and, stepping back one generation, even his teacher Matsumura Sokon. Matsumura was appointed into the service of the royal Family of the RyuKyu Kingdom, eventually becoming the chief martial arts instructor and bodyguard to the last three Okinawan kings. His links to Japanese martial arts was strong and he introduced both sword and staff systems in to Ryukyun traditional martial arts. Described by Funakoshi as having a “terrifying presence” he was also described by his student Anko Itosu as blindingly fast and deceptively strong.

Sokon Matsumura

For only a few, but influential years and as a teenager, Matsumura had studied under Sakugawa Kanga who, born in 1735 (or 1762 depending on who you study) was an Okinawan martial arts master, himself very much influenced by the Chinese White Crane system from his Chinese Kempo instructor ‘Kusanku’ (Kung Syang), after whom he named the Kata we are familiar with today and Takahara Peichin (1683-1760).

Satunuku (Kanga) Sakugawa

Satunuku (Kanga) Sakugawa

The term ‘Chinese Hand‘ was used to describe the fighting methods from much earlier time, later and for political reasons altered to the homophone of ‘Kara’ “empty hand‘ (Karate), by Funakoshi so as to make it acceptable to an emerging Japanese militaristic culture in the early part of the twentieth century. Matsumua’s birthplace, Shuri, itself a district in the City of Nahe introduces us to two of the three ‘foundation‘ styles of Okinawan ‘Te’ (hand), from which all the popular ‘mainstream styles of today have emerged. The terms Tode and Tuidi also described early Okinawan arts.

It is necessary to simply summarise the three ‘Te‘ systems, all based on regional situations – a fishing village in the case of Tomari-te, the district of Shuri-te (and old capital) and the city of Nahe-te. Many of the students and latterly masters of these systems even then ‘cross-trained,‘ Motobu Choki, (teacher to Wad-ryu’s founder, Hironori Otsuka) being a student in both Shuri and Nahe-te.

Motobu Choki

Motobu Choki

Naha-te, primarily based on Fujian White Crane and eventually formalised by Higaonna Kanryo was the forerunner of Goju-ryu. The successor styles to Shuri-te include Shotokan, Shotokai, Wado-ryu Shito-ryu Shorin-ryu, Shorinji-ryu and others. Tomari-te was very much a Chinese influenced style, supposedly an ‘underground’ fighting method and one of the really well respected masters Motobu Choki was a Tomari-te master. When the term Karate eventually took hold the practice of naming these systems after their area of origin declined, but it can’t readily be forgotten that what we know as karate today from its roots in Okinawa, had deeper roots going back to the 7th Century in Chinese Chuan Fa (Gung Fu).

There are two major events at which points Okinawan fighting methods turned a corner and we have alluded to these already, the first being when Itosu Ankowho was a part time teacher at an Okinawan primary school was instrumental in getting Karate introduced to Okinawan schools. Much modification of teaching methods was, understandably, required and the systematic methods we know today were introduced at this time (1901). He created the Pinan (Heian in Japanese) forms, also breaking down the older, large Naihanchi form (Tekki in Japan), creating the three modern versions practised today. In the early 1900’s, Itosu wrote his ‘Ten Precepts’ (Tode Jukan) of Karate.”

Ten Precepts

While Itosu did not invent karate himself, he codified the Kata (forms) learned from his master, Matsumura, and taught many karate masters. Itosu’s students included Choyu Motobu (1857–1927), Choki Motobu (1870–1944), Kentsu Yabu (1866–1937) who introduced karate to Hawaii, Chomo Hanashiro (1869–1945), Gichin Funakoshi (1868–1957), Moden Yabiku (1880–1941), Kanken Toyama (1888–1966) founder of the All Japan Karate-do Federation (AJKF), Chotoku Kyan (1870–1945) who was a participant in the 1936 meeting of Okinawan masters, where the term “karate” was standardized, and other far-reaching decisions were made regarding martial arts of the island at the time, Shinpan Gusukuma (1890–1954), Kenwa Mabuni (1887–1952), and Chosin Chibana (1885–1969) of Shorin-ryu fame.

Shinpan was head of the only Okinawan version of Shito-ryu. Kenwa Mabuni (1889 – 1952) was one of the first Karateka to teach on mainland Japan and is credited as developing the Japanese version and style known as Shito-ryu.

Kenwa Mabuni

The second corner that Okinawan turned and, probably, its most impactive, was its introduction into the Japanese university world by Funakoshi Gichin. However, it was Itosu that started the train of events that led, eventually to the Japanese taking over Karate as if it had always been its own. This was his letter (the Ten Precepts) to the Japan Minister of Education and Minister of War in 1908.

The second corner that Okinawan turned and, probably, its most impactive, was its introduction into the Japanese university world by Funakoshi Gichin. However, it was Itosu that started the train of events that led, eventually to the Japanese taking over Karate as if it had always been its own. This was his letter (the Ten Precepts) to the Japan Minister of Education and Minister of War in 1908.

Enter Funakoshi Gichin. Funakoshi had trained in both of the popular styles of Okinawan Karate of the time: Shorei-ryu and Shorin-ryu. Shotokan is named after Funakoshi’s pen name, Shoto, which means “pine waves” or “wind in the pines”. In addition to being a karate master, Funakoshi was an avid poet and philosopher who would reportedly go for long walks in the forest where he would meditate and write his poetry. Kan means training hall, or house, thus Shotokan referred to the “house of Shoto”. This name was coined by Funakoshi’s students when they posted a sign above the entrance of the hall at which Funakoshi taught reading “Shoto kan”. By the late 1910s, Funakoshi had many students, of which a few were deemed capable of passing on their master’s teachings. Continuing his effort to garner widespread interest in Okinawan karate, Funakoshi ventured to mainland Japan in 1922.

Funakoshi Gichin

Funakoshi Gichin

In 1922, the Japanese Minister of Education invited Funakoshi over to Japan to give a demonstration and in 1924 at Keio University was established the first University Karate club and by 1932 was present in nearly all Universities. During this time period, prominent teachers who also influenced the spread of karate in Japan included Kenwa Mabuni, Chojun Miyagi, Motobu Choki, Kanken Toyama and Kanbun Uechivery much paralleled by the rise of Japanese militarism and expansionism. Uniquely, though, it was also at this time that Karate received the ‘do’ appendage, distancing it from the ‘combat’ origins and recognising it as path to follow for other more enlightening reasons. We see this, of course, in Judo (Ju Jutsu), Akido (Aiki-Jutsu), Kendo (Kenjutsu) and Iaido from Iaijutsu.

Funakoshi changed the names of many kata and the name of the art itself (at least on mainland Japan), doing so to get karate accepted by the Japanese Budo organization Dai Nippon Butoku Kai. Funakoshi also gave Japanese names to many of the kata. The five pinan forms became known as heian, the three naihanchi forms became known as tekki, seisan as hangetsu, Chintō as gankaku, wanshu as empi, and so on. These were mostly political changes, rather than changes to the content of the forms, although Funakoshi did introduce some such changes. Funakoshi had trained in two of the popular branches of Okinawan karate of the time, Shorin-ryū and Shōrei-ryū. In Japan he was influenced by kendo, incorporating some ideas about distancing and timing into his style. He always referred to what he taught as simply karate, but in 1936 he built a dojo in Tokyo and the style he left behind is usually called Shotokan after this dojo.

The modernization and systemization of karate in Japan also included the adoption of the white uniform that consisted of the kimono and the dogi, or keigogi—mostly called just karategi—and colored belt ranks. Both of these innovations were originated and popularized by Jigoro Kano, the founder of judo and one of the men Funakoshi consulted in his efforts to modernize karate.

Karate Training with Shinpan Guskuma at Shuri castle, Okinawa c. 1938

In 1936 a fascinating meeting took place of many of the most senior Okinawan Karate masters to try and formalise and even understand what karate had become as it took on mainland Japanese form. Not all of them actually knew that the ‘Do’ (‘Spiritual Way’) suffix had be appended to it, when one reads the transcript, nor did all of them accept the change to the Kanji version of ‘empty hand.‘ In Okinawa it had since the early days been known as Tode or Toodii.

Eminent Okinawan Karate Masters 1938

Front Row L-R Chojun Miyagi, Chomo Hanoshiro, Kentsu Yabu, Choto Kyan

Back Row L-R Genwa Nakasone, Chosin Chibana, Choryu Maeshiro, Shinpan Shiroma

Extract From The Meeting of Masters 1936

Chojun Miyagi: There have been “Te” in Okinawa. It has been improved and developed like Judo, Kendo and boxing.

Kyoda Juhatsu: I agree to Mr. Nakasone’s opinion. However, I am opposed to making a formal decision right now at this meeting. Most Okinawan people still use the word “Chinese Hand” for karate, so we should listen to karate practitioners and karate researchers in Okinawa, and also we should study it thoroughly at our study group before making a decision.

Chojun Miyagi: We do not make a decision immediately at this meeting.

Matayoshi: Please express your opinion honestly.

Chomo Hanashiro: In my old notebooks, I found using the kanji (= Chinese character), “Empty Hand” for karate. Since August 1905, I have been using the kanji “Empty Hand” for karate, such as “Karate Kumite.”

Goeku: I would like to make a comment, as I have a relation with Okinawa branch of Dai Nippon Butokukai. Karate was recognized as a fighting art by Okinawa branch of Dai Nippon Butokukai in 1933. At that time, Master Chojun Miyagi wrote karate as “Chinese Hand.” We should change his writing “Chinese Hand” into “Empty Hand” at Okinawa branch if we change the Kanji into “Empty Hand.” We would like to approve this change immediately and follow procedure, as we need to have approval of the headquarters of Dai Nippon Butokukai.

Ota: Mr. Chomo Hanashiro is the first person who used the kanji “Empty Hand” for karate in 1905. If something become popular in Tokyo, it will automatically become popular and common in other part of Japan. Maybe Okinawan people do not like changing the kanji (= Chinese character) of karate. But we would be marginalized if the word “Chinese Hand” is regarded as a local thing, while the word “Empty Hand” is regarded as a common name for karate as a Japanese fighting art. Therefore we had better use the word “Empty Hand” for karate.

Nakasone: So far the speakers are those who have been living in Okinawa for a long time. Now I would like to have a comment from Mr. Sato, the director of the School Affairs Office. He came to Okinawa recently.

Sato: I have almost no knowledge about karate, but I think the word “Empty Hand” is good, as the word “Chinese Hand” is groundless according to the researchers.

Furukawa: The kanji written as “Empty Hand” is attractive for us who came from outside Okinawa, and we regard it as an aggressive fighting art. I was disappointed when I saw the kanji “Chinese Hand” for karate.

Nakasone: This time, I would like to have a comment from Mr. Fukushima, the Regimental Headquarters Adjutant.

Fukushima: The kanji “Empty Hand” for karate is appropriate. The kanji “Chinese Hand” for karate is difficult to understand for those who do not know karate.

Ota: There is no one who do not like the word “Empty Hand” for karate, but there are people who do not like the word “Chinese Hand” for karate.

The transcripts also indicate how little many of the masters knew of each others backgrounds. This meeting was a watershed in the history of Karate and effectively a ‘changing of the guard.’

Masters of Karate in Tokyo – 1930s

L-R: Kanken Toyama, Hironiri Ohtsuka, Takeshi Shimoda, Gichin Funakoshi, Motobu Choki, Kenwaa Mabuni, Genwa Nakasone, and Shinken Taira

The Modern Systems

Evolving from these beginnings we have the Karate systems that have managed to survive, pretty much in tact throughout most of the twentieth and into the 21st century and a study of Karate from this point needs to be done through the lens of these systems and their founders.

We hear, until we are fairly sick of the term, constant reference to ‘traditional’ karate, as if its history has an unbroken, technical integrity, where techniques have remained unchanged for millenia. The short dip into its Okinawan antecedents, with its Chinese influences and subsequent Japanese re-moulding to align it for wider, political ends, should disabuse anyone that there is some unalterable sanctity about the systems. They are the very changeable products of certain individual’s strong views on the direction and shape their Karate should take. It was when these individual ‘styles‘ ended up within the ownership of organisations that a snapshot photograph was taken of the system, never to changed from that day forward. Constant change would signal weakness and that wasn’t going to happen to very territorially motivated organisations; we’ve paid the price ever since.

Whilst not wanting to neglect the less well known, or smaller Karate systems, who I want to write about at another time, the following will be an overview of the following; Shotokan, Wado ryu, Shito ryu/Shukokai, Goju ryu, Kyukushinkai and Shotokai. This is the story of individuals and how, from the three Okinawan Todi te, we see these people resist, thankfully, the temptation to ‘consolidate’ karate into one homologeous system, as was the strong desire in the early twentieth century.

Goju ryu

I want to start with Goju, as it probably has stayed more true to its Okinawan/Chinese heritage than any of the other styles, for which we have to thank the efforts of Chojun Miyagi (1888-1953). A long-term student of Kanryu Higashionna (Higaonna), Miyagi, during trips to Fujinan province in China, took much of the Shaolin and Pa Kua systems, blending them into the unique Goju ‘hard/soft’ methodology and naming the style in 1929. He maintained that the kata Suparimpei contained the whole of the syllabus of Goju ryu, with the katas Sanchin and Tensho representing the hard and soft aspects of the style, respectively.

Gogen Yamaguchi

Gogen Yamaguchi

The transition of Goju ryu in Okinawa to Goju kai in Japan was in the hands of the famous Gogen Yamaguchi and his International Karate do Goju kai Association. Goju ryu’s cousin style is Uechi ryu, another style heavily influenced by Chinese martial arts and the product of Kanbun Uechi, who again studied in Fujinan province and was a product of the Naha-te, more circular method of movement. Goju is still far less ‘linear’ than the other major styles. The Kata Seanchin is from Uechi ryu, with Sanchin, Seisan and and Sanseirui coming from the Chinese Panga-noon(hard/soft) system, as with Goju.

Shotokan

We have the roots of the name described earlier and the system claims the ascendency, in many ways, certainly in the number of its participants world-wide and direct inheritance from the Karate of Itosu and Matsumura. The Karate that Funakoshi introduced into Japan would have still been recognised by his Okinawan contemporaries, but after his son Gigo (Yoshitaka) Funakoshi (1906-1945) had worked his personal magic, we very much had Japanese Karate. In came the low stances, body commitment to striking and a range of additional high kicks, such as mawashi geri, fumikomi, yoko geri keage and yoko geri Kekomi – all with a much higher knee lift.

Yoshitaka Funikoshi

Yoshitaka Funikoshi

He introduced chain, or combinations of techniques with emphasis on Gyaku zuki and more fighting oriented training drills such as the Kihon Ippon Kumite (1 step sparring), Jiyu Ippon Kumite, Gohon Kumite (5 step sparring) and Jiyu kumite, which he introduced in 1935. The publication in 1936 of the book ‘Karate-do Kyohan’ established the new Karate, now far removed from its Okinawan origins, with re-named, more Japanese sounding Kata and the Japanese homophone of Kara added to the name.

Its move to competition, however, was a step too far for the more ‘traditionalists’ within the Shotokan movement and the first split occurred between the Japan Karate Association (JKA), headed at that time by Masatochi Nakayama and the Shotokai faction of Shigeru Egami. Nakayama, through the JKA laid down the 27 Kata of the Shotokan system.

Funakoshi following in the steps of Itosu, wrote his 20 Precepts of Karate, supposedly the philosophy of Shotokan. In about 1924, Funakoshi adopted from Judo the Kyu/Dan rank system, white Gi and coloured belts and in the same year awarded 1st Dan to a number of his students, one of whom features in the development of the next style, Hironori Otsuka.

Otsuka in April 1924 receiving the first ever Ist Dan Black belt from Funakoshi Gichin

Otsuka in April 1924 receiving the first ever Ist Dan Black belt from Funakoshi Gichin

Wado-ryu

Hironori Otsuka (Ohtsuka), born in Japan in 1892 was a student not only of Funakoshi, but also of Kenwa Mabuni and Choki Motobu. He was something of a latecomer to Karate, but not to martial arts having been a Jujutsu student since the age of 5 and it was not until 1922 that he began his training with Funakoshi, recently arrived in Japan.By 1928 he was an assistant instructor at Funakoshi’s school, but a split occurred posibly as a result of Otsuka’s training with Motobu and a difference of opinion between him and Funakoshi over certain aspects of training, the parting of the ways coming in the early 1930’s. It was in 1934 that Otsuka opened opened his own karate school the Dai Nippon Karate Shinko Kai, blending his Karate with his previous knowledge of Ju Jutsu. This was Wado-ryu, a name that came a few years later.

Otsuka in later years

Otsuka in later years

In 1938/40, his style was registered at the Butokukai, Kyoto for the demonstration of various martial arts, together with Shotokan, Shito-ryu and Goju-ryu. Interestingly it was registered as “Shinshu Wadō-ryū Karate-Jūjutsu,” a name that reflects its hybrid character. The style very much reflects the ‘management’ of an opponent, exemplified in the principle of ‘tai sabaki’ and is, in general a more ‘balls of the feet’ and lighter style than Shotokan.

Otsuka originally designated just 9 official kata; Pinan Shodan, Pinan Nidan, Pinan Sandan, Pinan Yondan, Pinan Godan, Kūsankū, Naihanchi, Chintō, and Seishan. Other Kata are practised within the system such as Bassai (Passai), a Tomari-te kata, Rohai, Wanshu, Niseshi and Jitte. In 1964 the organisation joined the new Japan Karate-do Federation (JKF) as a major style and changed its name to Wadokai in 1967. The JKF had originated under the name FAJKO in 1964.

Otsuka died in 1982, leaving the system in the hands of his son…….

Wado like Shotokan has been very successful at spreading its net world-wide and the UK was fortunate in having been appointed with Otsuka’s most senior student Tatsuo Suzuki – more later.

Shito-ryu & Shukokai

As always in this study, we have to start with an individual who was responsible for the foundation of the style of Shito-ryu, in this case Kenwa Mabuni and Okinawan born in Shuri in 1889 and was a student of both Anko Itosu and Higoanna Kanryo. Originally, a student at the age of 13 of Shuri-te, but was close friends with Chojun Miyagi, who introduced him to Higaonna from whom he began to learn the Naha-te. Mabuni had other teachers and kata, particularly, was a great passion of his as was his desire to see karate installed in mainland Japan and it was under Mabuni’s influence that the name changed from Chinese to ‘empty hand.’ The title Shito was in honour of his two teachers and is an amalgam in Kanji of the first characters of the names of Itosu and higasionna.

Choju Miyagi

Choju Miyagi

Mabuni was, in no small way, helped in establishing Shito-ryu by another karate master and industrialist, Ryusho Sakagami (1915-1993), who financed the opening of clubs around the Osaka area. After his death, and no surprise, the Shito-ryu organisation split into competing factions, so many that to list them would would make one’s eyes water and the only uniquely different spin-off, which I will cover here is the Shukokai of Chojiro Tani.

Ryushu Sakagami

Ryushu Sakagami

Shukokai

Despite its technical differences, Shukokai cannot divorce irself from the Shito-ryu roots or similarities, Kata not being the least in the list and many international Shukokai organisations are ‘partnered-up’ with a Shito-ryu one. Its founder ChojiroTani (1921-1998), originally studied under Miyagi Chojun whilst a student at Doshisha University in Kyoto. When Miyagi returned to Okinawa it was Mabuni who took over the teaching and from whom, amongst other things he learned Shuri-te, as well as Shito-ryu. He was one of Mabuni’s senior students and received his certificate of succession from him, and although then head of Shito-ryu, he began teaching his own style, Shukokai, meaning ‘way for all.’ This was in 1946 at his dojo in Kobe.

Chojiro Tani on the right with his senior student Shigeru Kimura.

Chojiro Tani on the right with his senior student Shigeru Kimura.

Sensei Tani had to be one the very nicest of Instructors I’ve ever met and trained under and Kimura the most impactive

It was the dynamic, mechanical differences that Tani introduced, later refined by his most senior student Shigeru Kimura (more later), such as the now almost infamous ‘double hip.’ Since Tani and Kimura’s death in 1995 many Shukokai organisations exist around the world today, some very closely aligned with Shito-ryu ones.

Kyokushinkai

A late starter in the pantheon of modern Karate systems, founded in 1964 by the Korean/Japanese master, Matsutatsu Oyama. The style is recognised as a full contact, or ‘knockdown Karate’ competitive system, supported by very tough, but practical training. It’s estimated that could be as many as 12 million practitioners of the system worldwide. Born in 1927 in Korea, during the long period of Japanese occupation, it was not until Oyama emigrated to Japan hat he began his Karate training under Funakoshi receiving his 2nd Dan in Shotokan. Also schooleds in Aiki-jutsu, it was after the war that he trained under a Korean instructor, but in Goju-ryu.

A young Mas Oyama

It is easy to see, however, the influence of other combat sports such as boxing, Thai and kickboxing in the competitive arena. Although originally allowed, following a level of unacceptable injuries, punches and elbows to the head are not now allowed, especially as no gloves are worn by fighters. Head kicks and knee strikes to the head are allowed. The system has a full range of kata, divided into Northern (Shuri-te/Shotokan) and Southern (Naha-te/Goju) kata.

Oyama’s own, very personal style developed after periods of isolated training and contemplation in the mountains and in the early 1950s he travelled, particularly to America, demonstrating his. In 1953, he formally resigned from Goju-ryu. In a ceremony in 1957, he formally named his style ‘Kyokushin’ and then in 1964 founded the ” International Karate Organisation Kyokushinkaikan” (commonly abbreviated to IKO or IKOK), to organize the many schools that were by then teaching the Kyokushin style.

No system has probably suffered from as many damaging splits into, supposed, ‘world-controlling’ organisations, as has been the case with Kyokushin since Oyama’s death in 1995. At the last count I think there were 5 official World Championships being held.

Shotokai

No system occupies such an awkward niche as does Shotakai. It claims, not unreasonably to be the real inheritor of the original Shotokan of Funakoshi and, to be fair, before his death Funakoshi was in a separate camp to certain factions of the Shotokan community.

originally, Funakoshi named his original association Shotokai in 1930 (Dai Nihon Karate-do Kenyukai) and Dai Nihon Karate-do Shotokai (NKS) since 1936, it being Funakoshi’s training hall that had the Shotokan name, ‘Kai’ meaning group – hence Shotokai. The group were a collection of senior students of Funakoshi who had begun to distance themselves from Nihon Karate Kyokai (NKK) better known outside Japan as the JKA, originally formed in an attempt to bring all Japanese karate under one roof.

Senseis Egami and Harada 1954

Upon Funakoshi’s death, the association split, broadly into the JKA faction and the Shotokan Association (Shotokai). There had emerged, by that time, however, some philsophical differences (such as the introduction of competitions and sport Karate) between the more modernising faction (NKK) now led by Senseis Nakayama and Nishiyama and the Shotokai (NKS) camp of Shigeru Egami (1912-1981). Egami, assisted by another of Funakoshi’s top students, Motonobu Hironishi continued the development of the art, editing it to be a much more relaxed and supple style than the very physical, muscularly demonstrative one of Gigo Funakoshi.

That work carries on today in the hands of Misusuke Harada MBE (1928-). Harada received his 5th Dan from Funakoshi in 1956 and is the only surviving Instructor with that honour. In 1955 Harad left Japan to spread Shotakai initially in Brazil and then Europe, where he still teaches today. Another Shotokai master Tetsuji Murakami had arrived in Europe prior to Harada and both organisations functioned in Parallel until Murakami’s death in 1987

In the words of the late Master Genshin Hironishi (5th Dan Shotokai Karateka and President of the Shotokai in Japan):

“Karate must be nearly as old as man, who early found himself obliged to battle, weaponless, the hostile forces of nature, savage beasts and enemies among his fellow human beings. He soon learned, puny creature that he is, that in his relationship with natural forces accommodation was more sensible than struggle. However, where he was more evenly matched, in the inevitable hostilities with his fellow man, he was obliged to evolve techniques that would allow him to defend himself and, hopefully, conquer his enemy. To do so, he learned that he had to have a strong and healthy body. Thus, the techniques that he began developing – the techniques that finally became incorporated into karate-do, are a ferocious fighting art but are also elements of the all-important art of self-defense.”

Foreword to Master Gichin Funakoshi’s book, ‘Karate-do, My Way of Life’

Karate in the UK

There is no escape from personalities and the person who looms large in the early days of karate in Britain is Vernon Bell (1922-2004). A founder member of the Amateur Judo Association, in 1949 he became a professional Judo coach, grading to 1st dan in 1952, training with one of the Judo greats, Kenshiro Abbe.

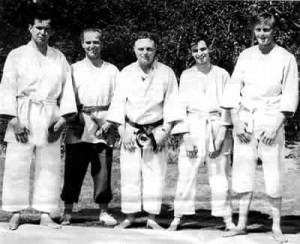

Vernon Bell and some of his early Karate students in 1957

Vernon Bell and some of his early Karate students in 1957

It was in the mid-fifties, however, that Bell first came across a photograph of a Japanese Karateka breaking wood with his foot. He began a regular pilgrimage to Paris to train with Europe’s Karate pioneer, Henri Plee and a Hiro Mochizuki a Yoseikan karate instructor from Japan. The first BKF dojo opened at the British Legion Hall in Upminster, attracting 10 students – Bell was very selective about new members and even by the end of 1959, there were still only 56 students registered in the Federation.

It was 1957 when he became the first Briton to hold a black belt in Karate and formed the British Karate Federation (BKF), that was originally affiliated to the French Karate Federation, but has remained since then the officially recognised governing body for Karate in the UK and the body to which the English, Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish governing bodies affiliate. It was 1963, that under the captaincy of Terry Wingrove, the British Karate Federation team took part in the first European Karate competition in Paris.

The seminal moment came in 1965 when Bell arranged for a demonstration team from Japan to come to the UK, also securing permission for the JKA’s Grand Champion Hirokazu Kanazawa to stay for a year and teach in the UK. In 1966, much to Bell’s regret the bulk of the members left the BKF to join the newly founded Karate Union of Great Britain (KUGB), where Kanazawa and now Keinosuke Enoeda were teaching Shotokan. Bell went back to teaching Yoseikan. Bell’s first love was his Ju-Jitsu in which he reached 10th Dan.

Hirokazu Kanazawa (1931-)

Keinosuke Enoeda (1935-2003)

On the Wado-ryu front, and in 1964 three Wado Japanese from Nihon University club visited London to demonstrate their art at the Shinto-ryu Kendo Club in London – these were Tatsuo Suzuki, Hajime Takashima and Toru Arakawa. In 1965, Suzuki returned to England to stay, followed closely by other Wado Japanese, such as Masafumi Shiomitsu. In 1966, both T. Takamizawa and Hayakawa transferred to the UK to help Mr Tatsuo Suzuki and Mr Masafumi Shiomitsu meet the growing demand for quality Wado-Ryu Karate. In 1968 Mr K. Sakagami, followed by Mr Kobayashi in 1969, also arrived in the UK, whilst Mr. S. Suzuki travelled to Ireland; furthermore, Mr Maeda arrived in the UK.

In 1964 Mr Tanabe was sent to the UK as an official delegate of the Japanese Karate Federation, where he founded the All Britain Karate Association. This was the first Wado-Ryu Karate organisation to be established in Europe. Mr Tatsuo Suzuki soon followed, when he moved to London to teach Wado-Ryu Karate. Wado in the UK was organised within the All Britain Karate Association (ABKA) until 1970 when Suzuki moved away and established the United Kingdom Karate-Do Federation, which later changed its name to the United Kingdom Karate-Do Wado-Kai, and became affiliated to the Federation of European Wado-Kai’s.

L-R: Wado-Ryu Sensei M.Shiomitsu, Tanabe, Tatsuo Suzuki, K.Sakagami, S.Suzuki, F.Sugasawa

L-R: Wado-Ryu Sensei M.Shiomitsu, Tanabe, Tatsuo Suzuki, K.Sakagami, S.Suzuki, F.Sugasawa

After a short period of time most of the other Japanese instructors joined the United Kingdom Karate-Do Federation, with the exception of Mr T. Takamizawa, who formed his own Karate organisation. Mr Masafumi Shiomitsu chose to transfer his teaching from the UK to France and then Madagascar. Nevertheless, Mr Masafumi Shiomitsu returned to the UK in 1976, and joined the United Kingdom Karate-Do Wado-Kai.

However, in 1989 Mr. Masafumi Shiomitsu expressed dissatisfaction with the direction taken by Wado Karate in the UK. Hence, he chose to leave the United Kingdom Karate-Do Wado-Kai in order to form the Wado-Ryu Karate-do Academy. Mr K. Sakagami, Mr T. Takamizawa, and most of the senior British Dan grades decided to join the new Wado-Ryu Karate-Do Academy. However, after a short period of time, Mr K. Sakagami (another really very nice person) decided to leave the Wado-Ryu Karate-Do Academy and formed his own organisation known as the Wado-Ryu Aiwakai Karate Federation. This has led to the creation of three major Japanese-led Wado-Ryu Karate organisations in the UK:

- The United Kingdom Karate-Do Wado-Kai, led by Tatsuo Suzuki Hanshi 8th Dan, which is affiliated to the Wado-Ryu International Karate Federation, and its Chief instructor is Tatsuo Suzuki Hanshi 8th Dan;

- The Wado-Ryu Karate-Do Academy, led by Masafumi Shiomitsu Hanshi 8th Dan, which is affiliated to the Wado-Ryu Karate-Do Federation, whose chief instructor is H. Ohtsuka II, Grand Master Wado-Ryu Karate-Do, 9th Dan.

- The Wado-Ryu Aiwakai Karate Federation, led by K. Sakagami Sensei 7th Dan, which is affiliated to the Japan Karate Federation Wado-Kai, H.Q. Japan.

In 1969, dissatisfied with the Japanese and having broken away from their control and the very much London centric leaning of the BKA (run at that time by Len Palmer – a true gentleman) many of the North of England clubs established the first Shukokai organisation in England, the Shukokai Karate Union (SKU),the decision being made by Roy Stanhope, and his senior instructors (myself being one). This coincided with the arrival on these shores of Shigeru Kimura, through his connection with Scotland’s Tommy Morris.

Shukokai Honbu Dojo 1964. Sensei Kimura is 2nd from left on the front row

Shukokai Honbu Dojo 1964. Sensei Kimura is 2nd from left on the front row

My own links into this fascinating sub-culture of society, go back to 1964 when, as a thin 15 year old schoolboy I joined one of the very first karate clubs in the north of England run as a partnership by Danny Connor and a Martin Stott. This was in a former Conservative club in the area of Ancoats, Manchester. Roy Stanhope was, at that time, a brown belt and still not a full-time instructor.This was at the start of the influx of Japanese Instructors to the UK and we had regular visits from Suzuki, Shiomitsu, and Takamizawa.

Roy Stanhope

This was a Wado club, a part of the ABKA (later to become the BKA) and after Danny departed to the far east for a few years and a split occurred between Roy and Martin (who eventually ceased teaching). The northern BKA clubs fell under Roy’s control, (and for whom I taught for many years, as well as running my own clubs), and eventually formed into the SKU. Roy was one of the most naturally competent and technically perfect Karateka the UK has produced – a real stylist, a fast and aggressive competitor as well as a perfectionist in the kata arena, who went on to be manage and coach the Gt. Britain Karate Squads.

This was a Wado club, a part of the ABKA (later to become the BKA) and after Danny departed to the far east for a few years and a split occurred between Roy and Martin (who eventually ceased teaching). The northern BKA clubs fell under Roy’s control, (and for whom I taught for many years, as well as running my own clubs), and eventually formed into the SKU. Roy was one of the most naturally competent and technically perfect Karateka the UK has produced – a real stylist, a fast and aggressive competitor as well as a perfectionist in the kata arena, who went on to be manage and coach the Gt. Britain Karate Squads.

As outlined above, it was the rump of the BKA that Roy formed into the SKU, itself eventually suffering breakaways, but still going strong under the control of Stan Knighton 9th Dan Shukokai. I noticed a huge difference in both the methods of teaching and attitude to students with the Shukokai Instructors – Tani, Kimura, Nambu, Ikazaki and Suzuki. In 1991, I took over as Chief Instructor of the BKA which Danny Connor, having returned from the far east, had received permission from Len Palmer to take over. I left in 1993 to run, with Geoff Thompson, the British Combat Association (BCA) and the rest, as they say, is history.

Thoughts on Styles

On the one hand, having a variety of styles of karate has contributed to its richness and diversity, but the unfortunate consequence has been the never-ending, political splits and territorial protectionism that ‘dogs’ the game today. We seem to have learned nothing over the years and on the world stage, the situation is as bad as it has ever been. Interestingly, Funakoshi almost predicted this state of affairs; in Karate-Do: My Way of Life he wrote “One serious problem, in my opinion, which besets present day karate-do is the prevalence of divergent schools. I believe this will have a deleterious effect on the future development of the art … There is no place in contemporary karate-do for different schools … Indeed, I have heard myself and my colleagues referred to as the Shotokan school, but I strongly object to this attempt at classification.” He goes on to say that all karate is one and that he feels rigid styles would be decisive and detrimental to karate’s progress (nice prediction!). So once karate has found its acceptance, Funakoshi was keen to foster a unity, was not keen on styles, and was not happy at being called Shotokan. He was totally fine with variations though and his objection to styles was not in order to create a homogenous art, but to avoid such a thing and the corresponding stagnation i.e. keep karate fluid and avoid that art becoming fixed into divided camps. All of which means he would no doubt agree with the sentiments expressed in these opening paragraphs.

Funakoshi also said, “Times change, the world changes, and obviously the martial arts must change too.” He was also an advocate of ‘cross training’: “Both Azato and his good friend Itosu shared at least one quality of greatness: They suffered from no petty jealousy of other masters. They would present me to other masters of their acquaintance, urging me to learn from each the techniques at which they excelled.” Both of those quotes are from Karate-Do: My way of life.

How Styles Evolve

Karate is a personal experience and exists only as the product of numerous individual’s thoughts, practices, beliefs and experiences. All styles as we know them today are simply variations on a theme, existing only as a consequence of certain strong willed instructors imposition of their thoughts as to how techniques, tactics and philosophy should shape future development. We only have to look at Gigo Funakoshi’s influence on Shotokan to see this in operation. Given this, we should not be presented with Karate as some historic and iconic monument, frozen in Amber. It is dynamic and given some key, fundamental principles which should remain as foundations it should be open to change, not just for change sake, but when, say, modern physical training sciences, especially the study of human mechanics, gives us the opportunity to improve impact, speed and fitness.

Naming styles has always been the start of the ‘protectionist box’ being built around a style and, often, this has happened almost by accident. We can take the Guju system as a good example of this. Miyagi himself did not give a name to his system until one of his senior students, Jinan Shinzato, was asked to name it following a demonstration he gave in Tokyo in 1930. Jinan Shinzato is said to have said struggled to accurately name the style he practised and it is said that he reluctantly settled on “Naha-te”, but felt this did not accurately reflect what Miyagi was now teaching. He returned to Okinawa, explained his predicament to Miyagi who decided that Goju-Ryu would be a good title for what they now practised.

Creating styles also happened retrospectively. It’s doubtful whether in the early days of the arts in Okinawa that people ever saw themselves as practitioners of Naha-Te, or Shuri-Te and it is now commonly accepted that these retrospective inventions and groupings were made by people further down the line and in keeping with the Japanese preference for the School/Ryu style clasification – ‘the naming of the thing’!

Peter Consterdine

Peter Consterdine